The Ikigai (生き甲斐 meaning of life) can be translated as “what is worth living for”, “the joy and purpose of life” or casually expressed as “the feeling of having something worthwhile to get up for in the morning”.

A thorough and often lengthy self-exploration in search for ones Ikigai is an important step for adulthood in the Japanese culture. It is a very personal process and the result can therefore vary greatly from individual to individual. Finding your personal Ikigai can result in feelings visibly communicated joy and pleasure of life combined with a very profound inner satisfaction.

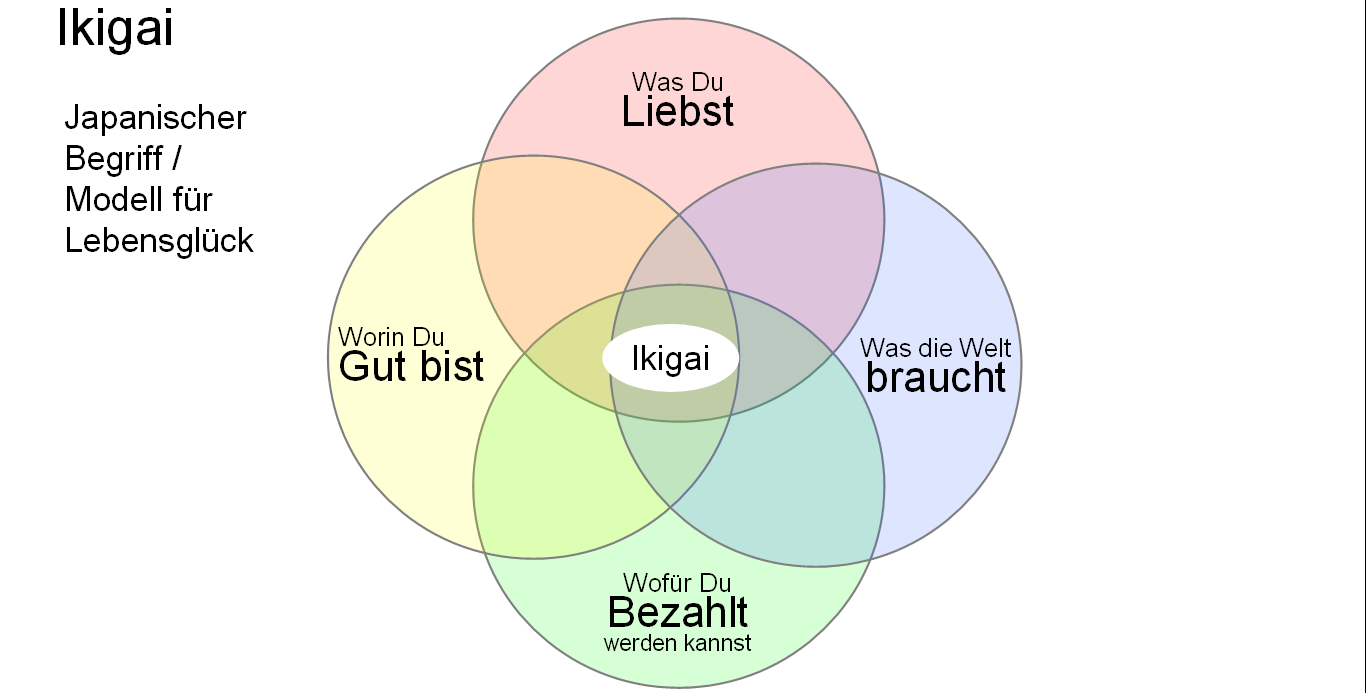

The very beautiful combination of four levels, that one experiences appreciation (and payment) for something that one can do, that gives one joy, that is needed and is good for the world, has also brought the term into the public consciousness in western industrial nations. It helps many people to look at these four levels together for the first time, which is why I like to use it in my value-based coaching processes.

Auf einen Blick - die Seitenübersicht

Development and meaning of the term

(Note: The following text is a summary of various sources, including a translation of the excellent German Wikipedia article on Ikigai, which I strongly encourage you to read. It contains more information than the English one)

Over time, the term ikigai assumed various meanings. In the Taiheiki it appears as early as the 14th century. But as many ideas of Japanese philosophy it was mainly oriented towards the aristocracy and upper classes, who would have the ressource and time to contemplate about the issues.

With the rise of the standard of living in Japan due to the post war economical boom of the 1960s, “ikigai” began to appear in books and in magazines.

Ikigai can have two different connotations. On the one hand, it refers to certain objects of interest, activities, or special circumstances that make life worth living (生き甲斐対象, ikigai taishō). On the other hand, ikigai also refers to the feeling of having reached this state of joy in life (生き甲斐感, ikigai kan).

In this meaning, from a Western perspective, it corresponds to a subjective sense of well-being that encompasses the English „Ppurpose of Life“ including “the joy of being alive. In German it would be “Lebenslust” and “Lebenszweck,” in French „la joie de vivre“ and „raison d’être“.

Japanese Tradition

At the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s – during a period of clearly perceived material abundance in Japan – newspaper articles addressed the “difficulty” of finding ikigai in a situation where everything was abundantly available at all times. Since this situation changed again due to a downturn in economic conditions, the media discussion of this “problem” also receded into the background again.

Individual needs versus social needs

Various authors have commented on ikigai, often basing it either on Ittaikan (一体感, ‘(group) sense of belonging,’ ‘oneness with the group’) or on Jiko Jitsugen (自己実現, ‘self-realization’). These connections will reflect the philosophical standpoint of the authors and their perspective on the Japanese society.

In 1985 Hamaguchi introduced the terms „kanjin“ and „kojin“.

Kanjin is a person whose identity roots in the relationships between him*herself and others. This corresponds to the sociocentric Japanese identity.

Kojin is a person who understands himself as an autonomous and independent being, a common concept in Western cultures.

This self-image is already instilled in children: While in Japan children learn shūdan seikatsu (集団生活, ‘group life’) at all stages of development West societies encourage more individuality.

Examples of different views

Clinical psychiatrist Kamiya Mieko (1914-1979) claims that ikigai cannot also be found as an adaptation to a social role, for example, as a mother. In her book she points out that there are people who consciously give up their previous social position in order to lead a completely different life. This might be by following a new or old vocation, for example becoming a missionary or by leaving behind family and friends as an explorer in order to live and work in a foreign country within a foreign culture.

The Buddhist Nikkyō Niwano (1906-1999), founder of the Risshō Kōseikai (立正佼成会 “Society for the Establishment of Law and Human Relations”) organization and an advocate of ittaikan puts the family and its environment above all. External work life is contrasted to the internal producuctivity of a family, their leisure, cohesion and altruistic sacrifice to one another, which he sees as the natural source of ikigai.

In his unreferenced 1969 tract, for example, he writes that seniors should also continue to contribute actively to community life in this context and “do something for others rather than have others do something for themselves.” Nikkyō thus argues for a democratic, (non-military) disciplined Japan in which the individual’s ikigai grows primarily through his role in the group.

Psychiatrist Tsukasa Kobayashi (b. 1929) supports Kamiya’s view, but argues in harsher terms against the conventional norms of Japanese society. For him many company employees behave like work robots, succumbing to the illusion that their actions support their family, their company and Japan, and that they find their ikigai in this. But at the end of the work process, they would discover that they could easily be replaced and that in reality they had not led a real life. Ikigai, he said, could not be achieved through material goods, but requires a “freedom of spirit.”

Strange limitations

Ikigai is sometimes mistakenly associated only with the workplace or the extensive practice of hobbies like “gateball” (ゲートボール, Gētobōru, a popular senior citizen sport), caring about your garden and flowers or writing haiku. In Japanese these ideas would be rather named hatarakigai (働きがい, the feeling that one’s work is worth doing) respectively asobigai (遊びがい, gimmicks worth spending time on).

But Ikigai is more: transcending the complexity of human life experience and its turmoils, ikigai is the feeling of a trtue satisfaction of desires and expectations, of love and of happiness – alone or together with other people.

Kamiya and Tsukasa present a rather Western view, in which they understand the modern Japan like an America freed from negative aspects, without violence, drugs and cynicism, in which the individual – without coercion by society – can live his own dream.

Anthropology and Ikigai

In the early 1990s, Gordon Mathews, an American professor of anthropology, compared the presentation and perception of ikigai in the Japanese media while conducting on-site interviews on the subject. He found that over time, magazine articles and books focused more and more on „jiko jitsugen“, while in his interviews, personal ikigai was more strongly associated with ittaikan. Mathews interprets this in his publications as a slow change in Japanese society, but one that was individually acknowledged and perceived with delay (lag phase).

Ikigai as a challenge in retirement

For several decades, there have been efforts in Japanese companies to help older employees find ikigai. The need for this assistance from employers is exemplified by the “Shōwa-hitoketa men” (昭和一桁), which corresponds to the generation born around 1926 to 1935. It was this generation that, through hard work and without much leisure time after World War II, laid the foundation for Japan’s later burgeoning economy. Shōwa-hitoketa men are characterized as “…can’t dance, can’t speak English, only know how to follow orders, eat everything put on their plate, and find their ikigai only in work.”[2] When they reach retirement age and the familiar routine of work falls away, they also lose their ikigai, they are prone to depression, and they become a burden to those around them-especially their wives.

However, the organized external help in the search for Ikigai also has opponents who take the position that in such a personal matter of self-discovery and self-realization, assistance or Ikigai training is ridiculous and in principle contradicts the very concept.

The Ohsaki Study

Toshimasa Sone and associates from the Department of Medicine at Tōhoku University, Sendai, Japan, conducted a seven-year longitudinal study beginning in 1994 of 43,391 adults (ages: 40 to 79), whom they surveyed regarding, among other things, ikigai. The researchers paraphrased the term as “belief that one’s life is worth living”; possible answers were yes, unsure, or no.

During the study period, 3,048 subjects (7%) died. The statistical analysis that followed also took into account factors such as age, sex, education, body mass index, cigarette and alcohol use, physical exercise, employment status, perceived stress, medical history, and a self-assessment by the subjects of their health. Nearly 60% of the study participants had said yes to feeling ikigai, and these subjects were mostly married, educated, and employed; they reported having less stress; and they rated themselves healthier.

The analysis of deaths showed that individuals who had indicated no in relation to ikigai had higher mortality than those who had answered yes. After categorizing the type of death, no-sayers had a significantly higher risk regarding cardiovascular disease and death from external factors; no significant difference was found between yes- and no-sayers for death from cancer. The study was published in 2008.

The study concluded that reporting a feeling of ikigai had the quality of predictive value: 95% of those with ikigai were still alive after 7 years, compared with about 83% of those who did not feel ikigai. Similar statements – a positive attitude towards life is related to physical health and thus to a higher life expectancy – are also confirmed by other authors.

( This subpage received its last update in June 2021. Most of this website is available in proper English translation. Should you come across a topic only available in German we recommend you to use your fovorite translation service. At the moment we recommend deepl . Should you have any question please let us know by sending an email to info@eis-coaching.com)